Writing Concisely

Concision and precision equal decisions

The philosopher Mortimer Adler held, “The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks.” Today, the ability to clearly and concisely communicate and advocate for an action on behalf of a decision maker is essential. Wasting a leader’s time with a poorly written decision memo is inherently disrespectful. The basic tenets of concise writing have not changed. However, they may need periodic review.

Short and Sweet

First, brevity. Clearly explaining a required decision in one page is difficult. During World War Two, Prime Minister Winston Churchill promulgated a memorandum on brevity. Despite the UK being in the midst of an existential battle, Churchill had to distribute the memo multiple times. Its text and structure are recreated below,

“To do our work, we all have to read a mess of papers. Nearly all of them are far too long. This wastes time, while energy has to be spent in looking for the essential points.

I ask my colleagues and their staffs to see to it that their Reports are shorter.

(i) The aim should be Reports which set out the main points in a series of short, crisp paragraphs.

(ii) If a Report relies on detailed analysis of some complicated factors, or on statistics, these should be set out in an Appendix.

(iii) Often the occasion is best met by submitting not a full-dress Report, but an Aide-memoire consisting of headings only, which can be expanded orally if needed.

(iv) Let us have an end of such phrases as these:

“It is also of importance to bear in mind the following considerations…”, or

“Consideration should be given to the possibility of carrying into effect…”.

Most of these wooly phrases are mere padding, which can be left out altogether, or replaced by a single word. Let us not shrink from using the short expressive phrase, even when it is conversational.

Reports drawn up on the lines I propose may at first seem rough as compared with the flat surface of officialese jargon. But the saving in time will be great, while the discipline of setting out the real points concisely will prove an aid to clearer thinking.”

Writing a short and crisp one-page memorandum is not easy. The 17th century philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote, “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.” Or in English, “I have made this [letter] longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.” Brevity requires time and work.

Avoid Fluff

The second tenet of concise writing is plain language. Business, diplomacy, and national security are inherently linked with our treaty allies, partners, and friends overseas, and brevity is not enough. We must write for the translators in sixth-grade English with short declarative sentences. Avoiding jargon, acronyms, sarcasm, subtlety, and innuendo. Our foreign counterparts may listen to our argument in English, but they will read and explain it to their bosses in their native tongue. So, we write for the translator—a gifted linguist, but without a background in business, diplomacy, or national security.

Keep it Simple

The third tenet of concise writing is simplicity—which is critical when dealing with difficult subjects with many components, some technical in nature. Then we should keep in mind the Physicist, Dr. Richard Feynman’s admonition that if you can't explain something to a first-year student, then you haven't really understood.

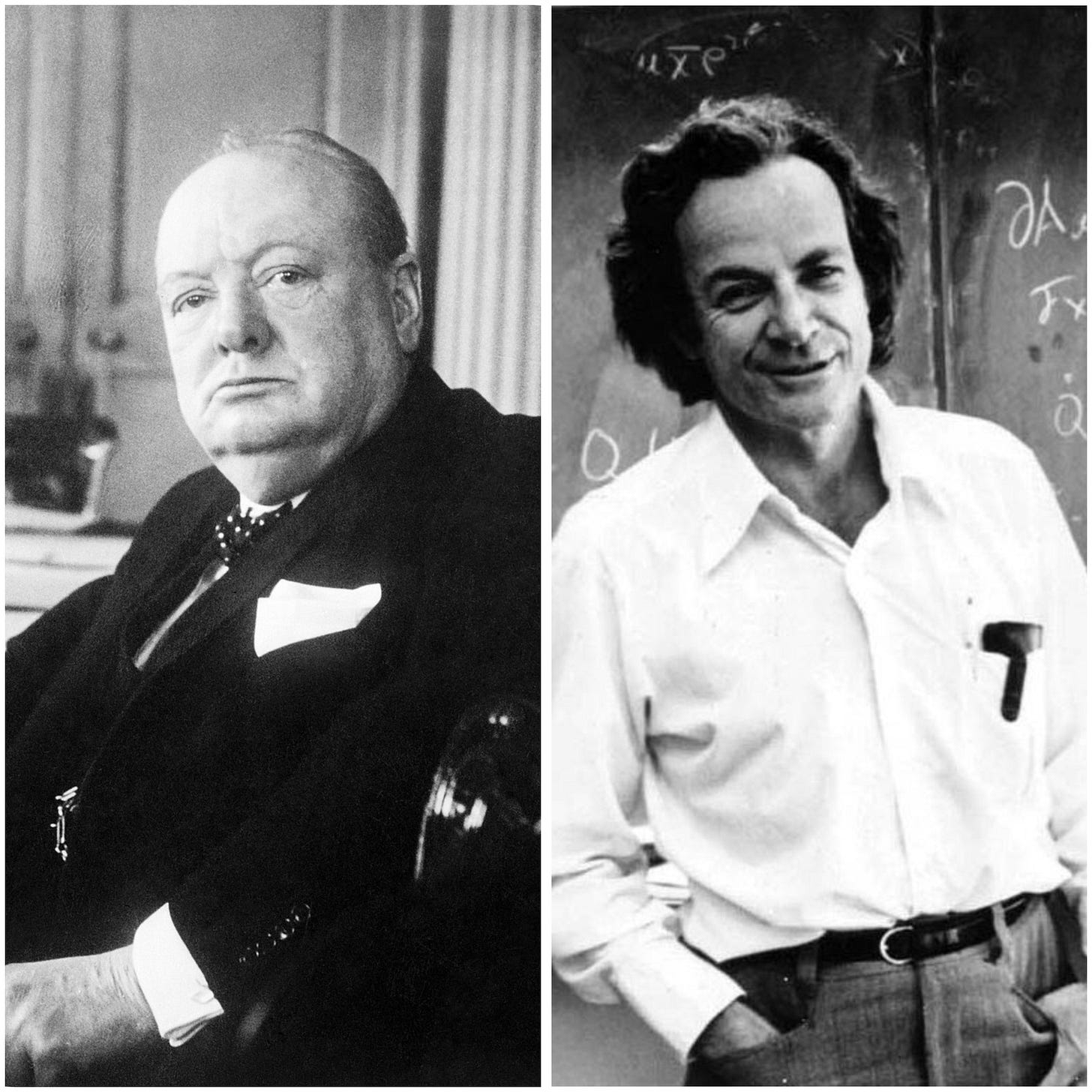

Left: PM Winston Churchill (Wikipedia), Right: Dr. Richard Feynman (Wonders of Physics)

Some experts with deep technical knowledge object to explaining their thesis in sixth grade English. They are more comfortable using a shared vocabulary of acronyms and jargon, which are meaningless to the rest. When I am told that brevity, plain language, and simplicity are not possible because of the complexity of the issue, I offer the following discussion of advanced drug discovery processes in the 1970’s.

In 1973, my second-grade teacher, Sister Shirley, said “Cathal, tomorrow you are going to tell us what your father does for work.” That night after dinner I asked, “how do I explain you are a drug discovery chemist, who runs fermentation byproducts screening at Eli Lilly pharmaceuticals?”

My dad put down his journal and said, “well let’s think about this.” Over the next thirty minutes my father walked me through the Feynman method. Professor Richard Feynman was a Nobel laureate in Quantum Physics and his method had four steps. First, read about a subject. Next, simplify it. Then, explain it to a child. When you fail, iterate.

The next morning, I said, “My dad, Dr. Sean O’Connor, talks to bugs. Very, very small bugs. He asks them very specific yes or no questions. Like do you kill the germs that cause pneumonia?”

All the hands went up and the questions began. “Where do you get the bugs?” “We pay people to dig up dirt around the world and mail it to us in boxes” I answered. “Can I get a job digging dirt?” “Yes, but you have to finish school first,” I replied.

“How do you grow the bugs?” “We pour the dirt into a metal bowl with water and sugar and keep it warm,” I explained.

“How do you ask the bugs questions?” came the next question. “We make bug juice.” “How do you make bug juice?” the class asked in unison.

“We spin the dirt, water, and bugs. Kind of like your clothes in the washing machine. We filter the dirt and the bugs out and we keep the rest.”

“What do you do with the bug juice?” the class asked. “We use it to try and kill germs.” “So how do you do that?”

“We pour clear Jello into clear plastic trays so that you can see through the Jello and plastic when you shine a light through it.

Once the Jello is solid, we spread a thin layer of germs on the Jello and put it in a warm box so the germs can grow. After the germs have grown, we shine a light through the Jello so we know how bright the light is before we use the bug juice.

Then we put one drop of bug juice on a small paper circle and lay it on top of the Jello. Then we put the tray with the Jello, and the germs, and the bug juice back in the warm box.

We wait for the bugs to grow and then we take out the tray, shine a light through the bottom of the tray and look at how much light shines around the paper circle soaked with bug juice. If the light is very bright the bug juice kills some germs, and if it is very dark the bug juice helps the germs grow.

That’s how my dad talks to bugs. Very, very small bugs. He asks them very specific yes or no questions. Like do you kill the germs that cause pneumonia?

Writing concisely is hard. Combining brevity, plain language, and simplicity is applicable to all topics, regardless of complexity. Our leaders require decision memos that embrace these three characteristics. It respects their time, provides additional decision space, and enables them to make better informed decisions.

Cathal is a Retired Rear Admiral. He has participated in Operations Restore Hope, Southern Watch, Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom and Tomodachi as well as disaster relief operations following typhoon Morakot in Taiwan, typhoons Ketsana and Megi in the Philippines and earthquakes in Padang, Indonesia.

An outstanding prescription and description! Loved the references to two excellent examples - Churchill (who could when necessary also write and speak with a flourish) and Feynman. I would specifically add my oft repeated advise as well especially for those just starting out, avoid using adverbs and adjectives as much as possible, sticking to subjects, verbs, conjunctions and objects. It will clarify and compress your writing - and they you can look for places were an adverb or adjective adds information.