Throwback Thursday

Brought to you by Special Warfare

An Encounter with History

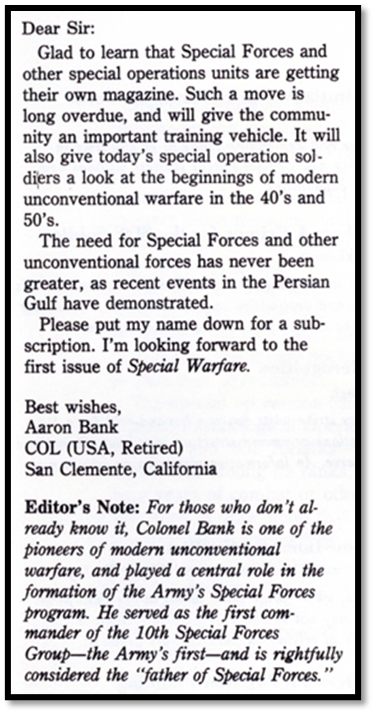

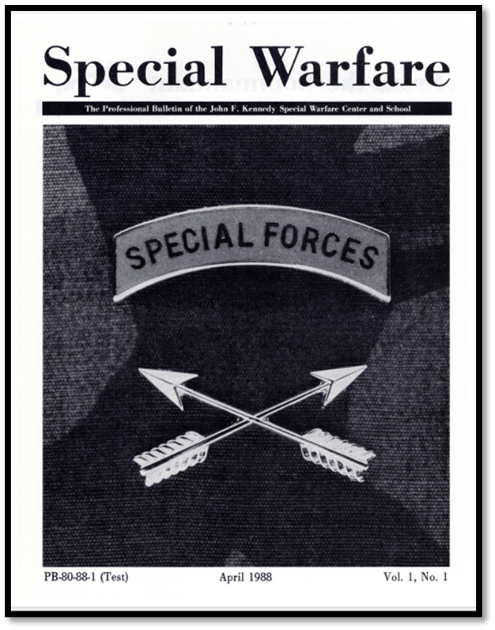

Recently, while going through the archives of the Special Warfare Journal, I noticed something interesting. In the journal’s very first 1988 issue, concealed among several “letters to the editor,” is a note from the “father of modern day Special Forces,” Col. (ret.) Aaron Bank. In it, he offers support for the branch journal and highlights its necessity as a mechanism of professional development. As a Co-Editor-in-Chief for the Special Warfare Journal, this was akin to reaching back in time and touching history.

As you continue to scroll through this legacy issue, you get a good idea of what the original mandate of the Journal was, something that we are getting back to with our most recent publications. Towards the end, in another reference to Col (ret.) Aaron Bank, I noticed a review for a book which is prominently displayed in my office, but which I have never read, From OSS to Green Berets, Col. (ret.) Bank’s memoir of his time in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and in Special Forces. Inspired by my tangible encounter with the ghosts of the past, I decided to finally read it. What I found was astonishing, the relevance of Bank’s experience conducting unconventional warfare in World War 2, and his experiences developing Special Forces, resonate strongly for special operations forces today. I was reminded of how quickly we forget our history when we refuse to look to the past for applicable lessons. Thus, I endeavored to write a review of the book, to highlight its lessons for members of the special operations community and wider Army.

From OSS to Green Berets: A Modern Review

Col. (ret.) Aaron Bank is known as the father of Special Forces. He was the first Director of Special Forces, and was the first commander of 10th Special Forces Group when it was activated in 1952. Before standing up Special Forces as the Army’s premier unconventional warfare capability, Col. Bank served in the OSS as a Jedburgh during WWII. In writing the book, Col. Bank wanted to tell the story of the OSS’s operational groups conducting unconventional warfare in WWII, and of the subsequent development of the Green Berets. His purpose in telling this story was to emphasize that the OSS and its legacy are intrinsically tied to that of the Green Berets, as the “operational predecessor” of US Army Special Forces.

There is no grandiose introduction in this book. Instead, Col. Aaron Bank lets his experiences speak for themselves. From the first sentence he dives right into the fascinating story of how he applied for a position with the OSS to get out of a boring position as a training officer for a tactical railroad battalion in Camp Polk, Louisiana. He wanted to liven up his career and exercise his foreign language capabilities, which the unit required. Needless to say, he had little idea of what lay in store for him. The memoir covers his training in clandestine activity, weapons and explosives, tradecraft, sabotage, and small unit tactics which became the backbone of the Jedburgh’s skills. From there he recounts his operational successes aiding resistance groups and guerilla networks in operations against the Nazis behind enemy lines in France.

After France’s liberation, Bank recalls an attempt to commence an unconventional warfare campaign in Germany, including a vague directive to capture Hitler from “Wild Bill” Donovan, the head of the OSS. However, the OSS canceled the mission just before it began. Equally fascinating are Bank’s vignettes from postwar Indochina. He details the complexities of a changing world order, his relationship with Ho Chi Minh, and their discussions about Vietnam’s future. He also describes run-ins with the French and British, highlighting uncertain alliances and shifting policies after the war.

Bank’s detailed account of the force development process for Special Forces provides valuable context into the creation of the Army’s unconventional warfare capability. These sections of the book are as close to the horse’s mouth as you can get, offering valuable insight into what Bank and his contemporaries were thinking. Interestingly, Bank went to great lengths to differentiate Special Forces from the Rangers, which senior leaders at the time consistently conflated. He painstakingly explained at every opportunity that while Rangers offered a limited, direct-raid capability into enemy lines, Special Forces operated in the deep, behind enemy lines for extended periods to develop, train, and fight alongside guerilla forces.

Additionally, Bank faced a myriad of challenges from senior leaders using doctrinal terms interchangeably, which obscured his vision for the branch. He lamented the fact that “the terms unconventional warfare, clandestine operations, unorthodox warfare, and special operations were being used interchangeably” (Bank 1986, 151). The incorrect use of doctrinal terms and definitions still plagues special operations today and will be a problem for CF-SOF I3 in LSCO without sufficient SOF integration into plans and operations before crisis.

From OSS to Green Berets is both entertaining and informative. The book’s first section, detailing Bank’s operations during and after WWII, reads like a military adventure novel. The portion on Special Forces’ development is drier but packed with relevant insights for the regiment and the broader special operations community. One disappointing aspect is the lack of mention of the First Special Service Force, from which Special Forces claims official Army lineage. This may have been intentional, as the 1st SSF had little in common operationally with the OSS, whom Bank emphasized as the model for the SF Groups.

Anyone interested in expanding their knowledge of UW and special operations history should read this book. For newly minted Green Berets, I would consider this required reading. One must know an organization’s past to effectively chart its future. For the modern SF regiment, I believe this will be an enlightening addition to one’s own professional library.

Note: Currently, this book is out of print. Copies are available online, but they are somewhat expensive. I recommend searching for copies of the book at local or professional libraries. It is also a worthy collector’s item if you have funds available.

Book Details:

Title: From OSS to Green Berets: The Birth of Special Forces

Author: Col. (ret.) Aaron Bank

Number of Pages: 216

Publisher: Presidio Press

Date: 1986

Special Warfare Journal Archives

Perusing the Special Warfare Journal Archives is a constant source of inspiration. Nowhere has it been made more apparent to me that “history doesn’t repeat, it rhymes.” At the Special Warfare Journal, we want our readers to have the ability to become inspired by our history in the same way. Thus, we have worked extensively over the last few months to update our physical and digital archives. Currently, our digital archives are completely up to date on DVIDs. Additionally, we have updated physical archives at the Special Warfare Journal Office and at the USASOC History Office. Finally, we have restarted our quarterly print publications (PB-80), which archive all online articles published in a given quarter. This allows us to continue our archiving of new content while continuing weekly publications on the SWCS website.

Whether you are a senior leader, or at the team level, we hope you will read these articles and harness takeaways to improve our formations. Special Warfare Journal, as the professional bulletin for ARSOF since 1988, is only as good as its community of authors/ readers. Let’s continue to make this a forum to drive innovation and change, share best practices, and hone our warfighting knowledge and skills!

Major John Byrnes is a pseudonym for a Regular Army Soldier and Civil Affairs Officer with a background in Infantry and Special Operations. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy and the National Defense University, and he currently serves as a Co-Editor-in-Chief for the Special Warfare Journal.

I took some quiet satisfaction during my career at the State Department upon learning that when the OSS was dissolved after the war, its research organization was transferred relatively intact to the State Department. There it became the Department of Intelligence and Research, later a Bureau. During the war it had gathered together academics and travelers to draw on their expertise and study newly gathered information as to what was happening and where. I served in INR as a watch officer and analyst in several capacities. It was still an interesting community.