The Frontline's Voice

The Unit's Role in the Professional Discourse Ecosystem

Units

There are no points for second place in combat. You win, or you lose. The more prepared you are, the better your chances.

The Army is in a unique and terrific spot in terms of its personnel and their experience. At the top, we have GWOT-hardened leaders who have kept an eye on and been preparing for potential peer conflicts for the last eight years or so. The bottom ranks are filled with tech-savvy and ambitious fresh blood with new ideas. Then, between the sage dinosaurs and the young fighter is the mid-level leadership that, collectively, has a healthy mix of both wisdom and ambition.

From deployments and CTC rotations to Sergeants Time Training in the backwoods of your local military installation, leaders empower subordinates to develop modern tactics, techniques, and procedures to fight and win on a rapidly changing battlefield. These proven or tested methods must be shared to facilitate institutional or organizational adaptation.

The collective insight from our muddy-boot-wearing soldiers is a critical element of the professional discourse ecosystem, facilitating healthy adaptation to face contemporary peers or problems. The units we serve in today have all been affected by this ecosystem in one way or another throughout the Army’s history.

Half-platoons

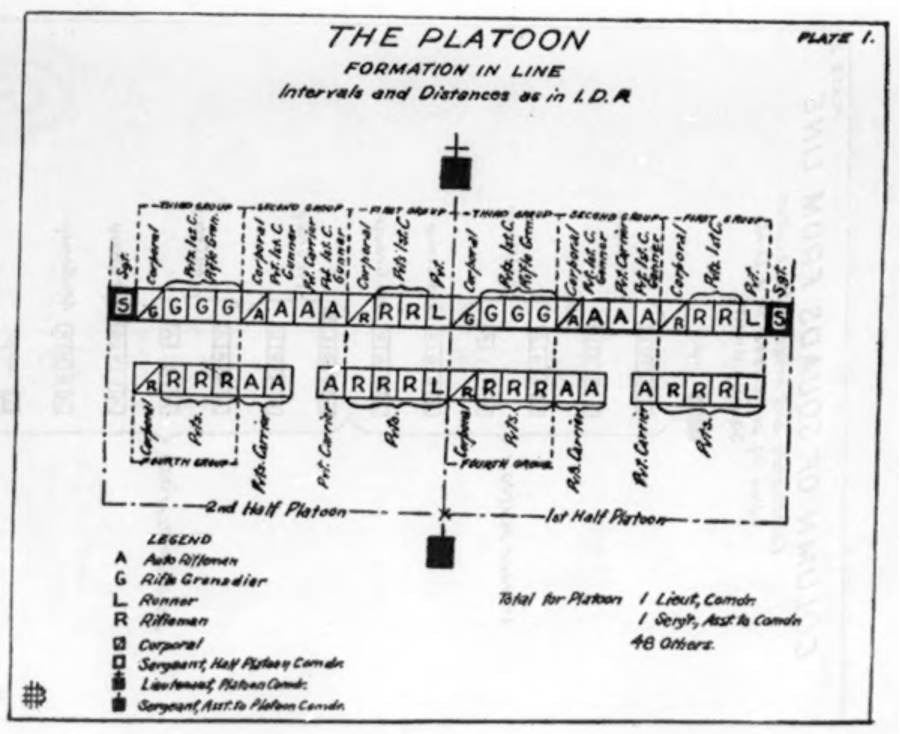

In World War One, the Infantry’s tactics and organization were codified in the Instructions on the Offensive Conduct of Small Units. This manual provided guidance and training that proved unfit for the rigors and changing character of warfare the doughboys would face in the European theater. Advances in technology and weaponry rendered the Infantry platoon's methods outdated. This image from “Fire and Maneuver,” in the July-September 2018 issue of Infantry, illustrates the organization of a rifle platoon from early 1918. With this structure, the unit’s grouping of similar weapons and personnel led to high casualty rates and overall ineffectiveness, which necessitated change if the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were to win.

In the spring of 1918, while in the rear, the AEF started experimenting with different formations to maneuver their troops during an attack. This new formation—the half-platoon—was designed to distribute weapon systems and capabilities equally to section-sized elements. This new method of organization would provide greater flexibility and speed in action. After relatively minimal training, these units quickly rotated to the frontlines and put these formations to the test. Among these troops was Major Henry H. Burdick, who successfully fought with these half-platoons during the Argonne Offensive.

After the war, Burdick captured this effective task organization and other techniques in the April 1919 issue of Infantry Journal in his article “Development of the Half-Platoon as an Elementary Unit.” I encourage every infantry soldier to read this article and observe the similarities between the half-platoon concept of late World War One and now.

Thank you, Major Burdick, for your contribution to the Army’s journals and for helping shape the lethal platoons I have been blessed to be a part of.

The Fighting Platoon Sergeant

One century after Burdick’s article was published in the Infantry Journal, then Captain Curtis Garner was doing the same thing—sharing his experience in what is now called Infantry. Published in the Spring 2020 issue of Infantry, Garner’s article, “The Fighting Platoon Sergeant Concept,” codifies a technique many infantry units across the force are familiar with. In many organizations, this concept is well known and has been adopted as common practice.

As Garner points out, ATP 3-21.8 The Infantry Platoon and Squad deliberately does not dictate the exact location of the platoon’s leadership, which allows for more flexibility. However, the Army’s institutions, such as Ranger School and Infantry Basic Officer Leader Course, teach that the Platoon Leader is to be with the decisive operation—the assaulting element and the Platoon Sergeant is to locate himself near the support-by-fire to facilitate MEDEVAC and logistical resupply. To ensure this equally if not more effective method, the “fighting platoon sergeant,” is taught at scale, I would encourage the Infantry Branch and its institutions to consider including this methodology in doctrine and lesson plans.

Get it out there

As we continue to prepare for potential contemporary conflicts, the saying “no plan survives first contact with the enemy” is espoused quite often. What if we could change that? What if the AEF had realized the half-platoon was a superior organization of troops prior to April 1917? How many lives would have been saved?

The ideas and experiences our soldiers have can lead to tremendous breakthroughs, but only if they are shared with the rest of the force. From there, the ownness is on the Army’s institutions to synthesize these collective insights and, if appropriate, use them to shape doctrine, policy, or lesson plans so we can truly share best practices in a practical manner—this is Army-wide adaptation at its finest. This is how the Army’s professional discourse ecosystem works, and it starts with the unit’s muddy-boot-wearing soldiers like Major Henry Burdick and Captain Curtis Garner.

We owe it to the next, or current, generation of warfighters to contribute the same.

Let’s hope you’re right.