Some Comments on the Recent Caribbean War

Weird content captures attention

Ten years ago, Ghost Fleet’s well-researched, fictional story helped jolt defense thinkers on the risks of large-scale conflict with China. In their recent War on the Rocks retrospective interview, Ghost Fleet authors P.W. Singer and August Cole explain how Fictional Intelligence, or “FICINT,” blends “research with narrative and explore … the future.” While Wikipedia and other sources credit Cole with FICINT, the use of future storytelling in the Army’s journals started at least as early as 1934.

81 years before Ghost Fleet, there was “Some Comments on the Recent Caribbean War” in the Winter 1934 issue of Infantry Journal. Ghost Fleet and “Some Comments” show that Army authors win attention when they deliver sound ideas in an unusual form.

Learning from unusual forms

Browsing the Winter 1934 issue of Infantry Journal, neither “The Tactical Problem of Alternative Positions in Event of Gas Attack” nor “The Grand Strategy of the World War (Part III)” would grab my attention. But “Some Comments on the Recent Caribbean War” hooks instantly. The title sparks questions: Which war? What comments?

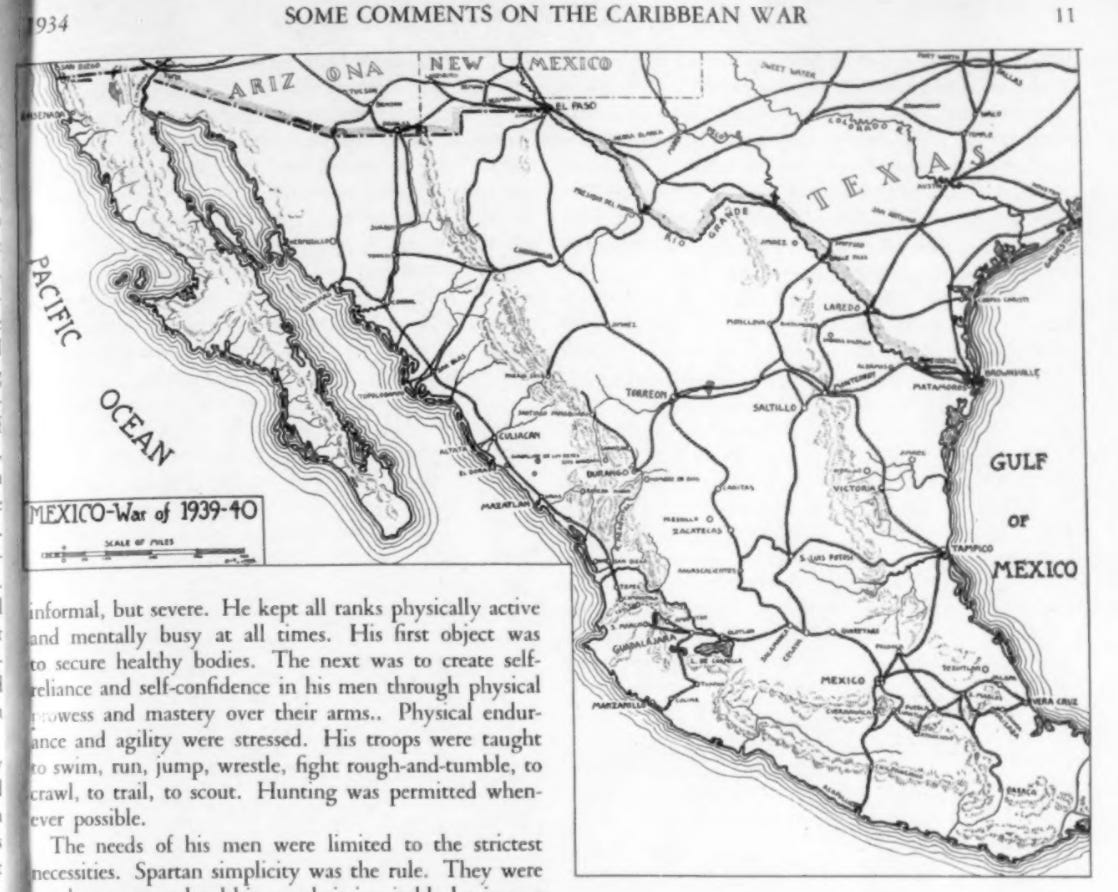

Pseudonymous author Brigadier General (ret.) Elmer Zilch deadpans through a fictional war to skewer the Army’s readiness and celebrate swift, mobile columns.1 Zilch’s point is not subtle. The article contrasts an “army lacking in discipline and overburdened with transportation” with “the brilliance of General Caldwell’s performance” as the commander of the West Coast Expeditionary Force.

Caldwell fields small, mobile, well-armed units that pull Mexican forces off balance and win. He practices what we’d now call mission command: he reorganizes on the move, keeps columns light, and still masses fast. With troops “inured to hardship,” each garrison becomes a “bandit stronghold” of trained, heavily armed soldiers. Airplanes connect columns, drop supplies, and evacuate casualties. Zilch concludes not just with a thunder run by Caldwell’s Light Division, but a clear call to action.

Zilch signposts his focus on light, mobile forces throughout, but is especially clear in his conclusion. In his view, the United States Army must reject “European worship of volume of fire.” He favors maneuver, drawing on the American traditions of the “Red Man, the Minute Man, the Virginia Rifleman, Jackson’s ‘Foot Cavalry,’ Forrest’s raiders, the Indian fighters, Western gunmen—even our modern racketeering gunmen.” He closes with a reminder of war’s early bloodshed as his spur to act now.

Make it interesting or lose the reader

Readers feel Zilch’s frustration with the status quo, and they keep reading because the form—a story—carries them. Zilch’s imagined after-action review and Ghost Fleet’s novel both use researched fiction to challenge orthodoxy without dry commentary or another unread white paper.

Zilch likely helped trigger Infantry Journal’s next-issue plea for “More Interesting Articles.” Interesting writing pairs original ideas with compelling form. Forrest Harding, the Harding Project’s inspiration, plainly agreed. In his first Mailing List, he encouraged articles in the form of “the intimate personal letter, the dialogue, and the narrative” to engage readers.

As you pick up the pen, think hard about your audience and the best way to reach them. Consider taking a few moments to hunt for inspiration in the back issues of your branch’s magazine. Old, interesting ideas are often ripe for reintroduction. You might also stumble across something weird that inspires a new approach: poetry, cartoons, valor citations, and much more.

Capture attention. Make an impact.

Army historian Brian Linn identified “Elmer Zilch” as the pen name of Joseph Marius Scammell for “Some Comments on the Caribbean War” in The Echo of Battle. The name “Elmer Zilch” was already a pop-culture wink—Ballyhoo magazine’s recurring everyman/mascot from 1931—so the byline itself signaled satire.