Motivation as a Choice

Orienting on Your Life’s Purpose

Over the past few weeks, a theme arose in my conversations with young soldiers, senior noncommissioned officers and warrant officers: motivation. I heard the full array. On the decreased motivation side- decreased drive and depression with regard to fitness; loss of motivation nearing retirement which resulted in apathy towards tasks, concerns over processes, and a lack of purpose; loss of motivation for service because of experiences with counter-productive leadership and toxic environments. On the increased motivation side- service members inspired to work harder because of promotions and career advancement; renewed efforts for self-improvement to be a better leader for their subordinates; inspiration for continued service because of career changing opportunities like submitting a U.S. Army Green to Gold packet or attending a selection and assessment program. Motivation centers around a driving force. This force directs people to remain persistent and oriented on specific goals. I noticed the soldiers, when talking about their motivation levels, shared a theme of connection, community, value, and most importantly, purpose. This is no revelation, as most would understand the aforementioned as key variables in driving someone’s motivation. The challenge is how to personally, or help someone, orient on life purpose to sustain motivation despite the environment. While it might not always feel like it, it’s a choice.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Motivation as a Choice

In Rick Warren’s book “Purpose Driven Life”, he writes, “The way you see your life shapes your life. How you define life determines your destiny”. He goes on to talk about how perspective defines how you use your talents, value relationships, and where you spend your time. I believe perspective and a clear personal life purpose is critical in shaping how you perceive and navigate your environment. The adage of “grow where you’re planted” is one way to look at approaching all experiences from the lens of “how can I make this moment purposeful and be of service?” The key is finding purpose in all circumstances by aligning it with your personal purpose. Your life purpose vice a situational purpose can be a strong motivator in goal-directed behavior when faced with de-motivating situations.

Life Purpose Versus Situational Purpose

Purpose is like climate versus culture- there is a short-term and long-term scaling. In the Center for the Army Profession and Leadership’s “Building and Maintaining a Positive Climate Handbook”, climate and culture are defined with clear distinctions. Climate is described as “day-to-day perceptions and feelings; affects motivation and trust of members; may be difficult to change but can happen quickly; shaped by direct leader”. Conversely, culture is defined as “deeply embedded beliefs and customs; long lasting and hard to change; shaped by strategic leaders”. Similar to climate, one can perceive their purpose in the moment or in a situation. This is the day-to-day environment. For example, a service member can feel a loss of purpose for a job or unit where they are unhappy or feel de-valued. It can be triggered by a bad interaction with a supervisor, harsh correction for a failure, or task misalignment of strengths and talents. If we were to look at this through the culture lens, the service member may be acutely feeling a lack of motivation and purpose situationally, but their life purpose, which is harder to sway with the immediate environment, can serve as an untapped well to draw the motivation they may be lacking. That service member can focus on their motivation for service in the Army, their passion for helping others, or their ability to solve problems. They can be further motivated by the opportunity to continue doing what they love in future assignments.

Choosing Intrinsic over Extrinsic Motivation

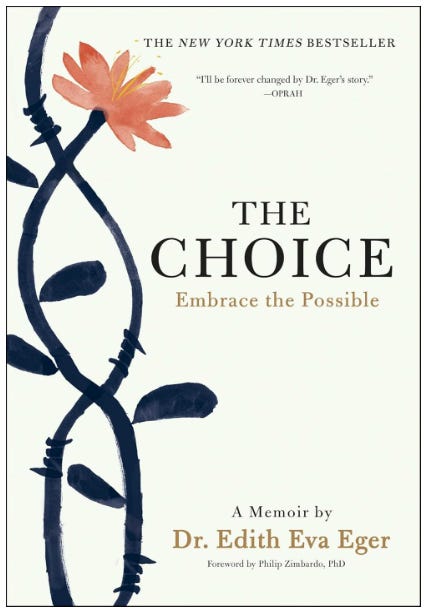

We have a choice in pulling from our purpose even in the midst of turbulent waters. Dr. Edith Eger- a Holocaust survivor pulled from a pile of corpses at Auschwitz during liberation- writes in her book “The Choice”, “You can’t change what happened, you can’t change what you did or what was done to you. But you can choose how to live now.” Choosing a mindset grounded in life purpose can help a servicemember maintain motivation even in the hardest situations. It is a conscious choice to seek motivation from within as opposed to seeking it from the environment. It is the difference between intrinsic (internal) and extrinsic (external) motivation.

I have wrestled with my motivation at times while serving, often triggered by counter-productive leadership, challenging situations, or jobs initially appraised as unfulfilling. I found ways to sustain motivation to get through those situations by reappraising through the lens of my life’s purpose. Working mobility operations while deployed in the Middle East required a balanced “art and science” approach as movement chains involve many nodes and stakeholders. From the art of honing communication skills to the science of reverse engineering systems, I assessed the work as cognitively stimulating and impactful. In the same vein, while assigned as the action officer to a lackluster task, I found motivation in the unexpected interactions and opportunity to coach soldiers and noncommissioned officers who were categorical strangers just a few hours prior. Both examples aligned with my personal life purpose of having impact, being of value, and serving those in need. By drawing on my life purpose, I sustained motivation in the good and bad.

Orienting on Purpose

Motivation can change like the weather if you let it. Allowing immediate external factors to decide whether you take action, put forth effort, or find value in accomplishing a task can be a short-sighted assessment of the situation. To help yourself or another service member with reinvigorating motivation, you should reassess if the feelings are situational or in misalignment with a life purpose and subsequent goals. Leaning on support networks and community such as family, friends, peers or mentors can make the hard experiences more manageable Deeply understanding your purpose can also help you engage in conversations with supervisors and leaders to help better align you to the right work or environments. However, when the situation cannot change, you can leverage your life’s purpose to maintain motivation.

Write it Down, and Read

Following a rapid deployment into U.S. Central Command, I returned feeling a loss of purpose and an emptiness that could only be explained by an abrupt shift in mission, responsibility, and hyper-vigilance. A mentor encouraged me to take a notebook with me on my next hike to think about and write down my core values, life purpose, and personal and professional priorities/goals. Doing so provided a vessel for introspection, personal clarity, and a tool for grounding my motivation. Additionally, I voraciously read for myself and to be well educated to help those in my formation. I read articles through the Harding Project’s outlets and From the Green Notebook on purpose and motivation throughout a career, and books on purpose and motivation like “Turn the Ship Around” by David Marquet, and organizational and leadership psychology, such as “Leadership: Theory and Practice” by Northouse. Coupled with my own journaling and writing, reading also gave me perspective on how others have navigated this space. It’s a Choice

While in a rather challenging time in my career, a mentor shared, “You always have control of three things: your attitude, your effort, and your professionalism.” Make the choice to pull motivation from within as it relates to the impact you want to have in life. It will help you put forth your best effort and sustain you through the inevitable challenging times. Set your sights beyond your immediate purpose in the situation and find new meaning through the perspective of your life purpose. It’s a choice.

Captain Melissa A. Czarnogursky is LTG (R) Dubik Writing Fellow and a Logistics Officer at FT Bragg, N.C. She commissioned from Seton Hall University Army ROTC with a BA in Psychology and a minor in Cognitive Science from Montclair State University. Her operational experiences include USAFRICOM, USCENTCOM and USINDOPACOM.

Great essay and message Melissa. I’d add that with the fleeting nature of motivation one must rely on choosing discipline. You’re not always going to be motivated but hopefully you’ve built healthy habits (at work and home) and have the discipline to maintain them.

you're right. motivation is always a choice. i think it comes after repetition