Let the Wookiee Win

Practical Advice for Military Writers

What should military writers do when their reader wants them to write poorly?

Several months ago, I was teaching a writing seminar at the US Army Command and General Staff College. We were discussing editing and style—how to make writing clear by choosing simple words that most people understand.

One student said, “I had a boss who told me to use bigger words to sound more professional. What should I have done?”

I explained that complex language makes writing harder to read and less professional, not more. Then I said, “Your boss is wrong, but you should do exactly as they ask. Use big words. Let the Wookiee win.”

A few weeks ago, I gave a writing talk to PME graduate students. The conversation turned to paragraph transitions, and I argued that most writers overthink them. A simple signal word or phrase is usually enough, and the best place for a transition is almost always in the first sentence of the following paragraph.

A student asked, “My advisor requires me to write a full transition sentence at the end of every paragraph. What should I do?”

I explained that ending a paragraph with a transition sentence is almost always awkward, wordy, and unnecessary. Then I said, “Your advisor is wrong, but you should give them what they want. Write the sentences. Let the Wookiee win.”

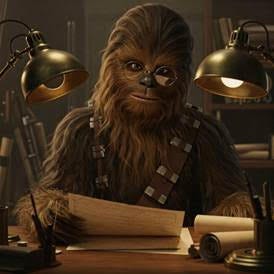

Photo courtesy of Dr. Trent Lythgoe

For the uninitiated, “Let the Wookiee win,” comes from a scene in the 1977 film Star Wars: A New Hope. In Star Wars, Wookiees are an 8-foot-tall, furry species known for their immense strength. The scene opens with a Wookiee named Chewbacca playing a holographic chess-like game against the droid R2-D2. When R2-D2 makes a strong move, Chewbacca becomes upset. C-3PO, R2-D2’s companion, insists the play was fair, but Han Solo, Chewbacca’s human partner, warns him, “It’s not wise to upset a Wookiee.”

When C-3PO objects, noting that nobody worries about upsetting a droid, Han explains, “That’s ‘cause a droid don’t pull people’s arms out of their sockets when they lose. Wookiees are known to do that.” C-3PO quickly reconsiders and tells R2-D2, “I suggest a new strategy, R2: Let the Wookiee win.”

In professional writing, the Wookiee is the reader; they get upset when they don’t get their way. And while readers won’t tear your arms off your shoulders, they will reject your writing. Bosses will send it back for revisions. Professors will give you a low grade. Editors will reject your article.

It’s not wise to upset a Wookiee.

As writers, it’s easy to resent our temperamental Wookiee readers. But in truth, we are Wookiees too. How often have you opened a book or started an article, only to stop after a lackluster sentence or two? The writer may have spent weeks, months—maybe even years—on that work, yet we discard it after a quick glance. It seems harsh and unfair, but we all do it. We have to because we’re busy.

Our readers are busy, too. We can sympathize with them, even if we don’t appreciate their methods when it comes to our writing. But ignoring them is a mistake if our writing is to achieve its purpose. Overwhelmingly, military professionals write for a purpose. Success isn’t about finishing the document—it’s about achieving the goal, which usually means satisfying a Wookiee or influencing their decision.

For example, I once wrote a paper urging a senior leader to replace an air MEDEVAC company in Afghanistan. The goal wasn’t to complete the paper; it was to get the decision my boss wanted. What I preferred to write didn’t matter. I was writing for a Wookiee (my boss) to persuade another Wookiee (three levels up) to act.

In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have to write poorly to placate Wookiees. Readers would judge writing on the strength of its arguments rather than its length, pomposity, or mindless obedience to arbitrary rules. They would value clear, concise, direct language over inflated prose. Military writers wouldn’t have to choose between good writing and keeping their arms attached. Good writing would be the standard.

Sadly, that’s not the world many military writers live in. Instead, they live in a military hierarchy where there’s always a bigger, stronger Wookiee. Writers at the mercy of these Wookiees must be ruthlessly pragmatic by always putting the reader first—even if it means sacrificing best practices. Winning the game—achieving the goal—means keeping the Wookiees happy.

Recently, a LinkedIn acquaintance told me his headquarters sent back his award recommendation because it was fewer than 82 words. I responded that minimum word counts are stupid and that judging recommendations, evaluations, or anything else by a word count is a mistake. What should my acquaintance do?

Let the Wookiee win.

After 30 years government service at State and DOD, I endorse this advice on points of style. Do be alert, however, for arguments about style that are camouflage for issues about content. This is a rare problem but it can happen. I once replaced my initials as drafter on a policy memo with those of the senior officer for whom I was writing a policy paper because I strongly disagreed with his requirements for the paper’s policy content. I disagreed strongly enough not to want to be identified with the paper.

Spot on! Let the Wookie Win! This is too awesome.